The Conferences

Nairobi,

1985

It was the largest women’s conference to date—and “brought the global women’s movement to Africa”

The Global Mood

By 1985, the end of the UN Decade for Women, global feminists had had the benefit of a decade of close collaboration through the UN World Conferences on Women. “It is difficult to find words to describe the impact of the UN Decade for Women on women around the world,” activist Peggy Antrobus later reflected, “It was life-changing for many and a watermark in public policies and programs.” It spurred laws against discrimination, shifts in domestic roles, the rise of women’s studies in universities, and broader access to jobs once closed to women.

Nairobi was envisioned as a culmination. After all, participants had the benefit of building and strengthening relationships, trust and understanding over the last ten years. Although the decade was over, the work had just begun. Women in both the Global North and Global South found themselves focused on economic issues and increasing fundamentalism; these convergences created common ground.

For the emerging global women’s movement, Nairobi was a critical moment—a chance to move from a global sisterhood into a more meaningful global solidarity among women. “I consider it to be the birthplace of global feminism,” says activist Charlotte Bunch.

"Wages for Housework" banner at a demonstration during the 1985 NGO Forum in Nairobi. (via Anne S. Walker)

The Planning: How Do You Organize a Global Milestone?

Nairobi was the largest UN Women’s Conference up to that point. It attracted 15,000 participants—one-third of them African. The conference, as participant Sia Nowrojee reflected, “brought the global women’s movement to Africa and African girls and women to the movement,” marking a pivotal moment of inclusion and connection.

And though the challenge was immense—bringing together 150 countries during a time of heightened Cold War tensions and economic crises—Nairobi was better-funded and better-organized than the first two conferences. Preparatory meetings, including a national conference for Kenyan women and a regional gathering in Arusha, Tanzania, played a key role in shaping the conference agenda. Women around the world mobilized, and African, Latin American, and Asian women organized early to ensure that their priorities—economic justice, land rights, and the impact of globalization—were central to discussions.

Mrs. Helvi Sipilä, Secretary-General of the 1975 Mexico City Conference. (via UN Photo)

The Players

The conference brought together a dynamic mix of feminist activists, government representatives, and grassroots leaders—including Leticia Ramos-Shahani, ambassador from the Philippines, who served as Secretary-General of the Conference; Dame Nita Barrow, the first female governor-general of Barbados who convened the NGO Forum; Eddah Gachukia, who chaired the Kenya NGO organizing committee; and Gertrude Mongella, the rising Tanzanian leader who later chaired the 1995 Beijing conference.

And of the 15,000 women who attended the Nairobi conference from all over the world, an estimated 5,000 were from Africa, with a large contingent of rural women. “Thousands of Kenyan women walked for miles from towns and villages across the country to Nairobi to participate in the NGO Forum,” Antrobus noted. There was strong representation, too, of women of color from the West, Indigenous women, and women representing liberation movements like the African National Congress (ANC), the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and the National Union of Eritrean Women.

Top: Thousands of women gather on the lawns of the University of Nairobi for the closing ceremony of the 1985 NGO Forum. (via Anne S. Walker)

Bottom: Members of the Bureau congratulate each other on the successful conclusion of the World Conference on Women, marking the end of the UN Decade for Women in Nairobi. (via UN Photo)

What Happened in Nairobi

Nairobi marked a concerted shift towards bridge-building and consensus despite deep global tensions. Conference leaders worked carefully to secure agreement on the Forward-Looking Strategies (FLS), a roadmap for women’s rights through the year 2000, while navigating intense political divides. Women from the Global South challenged Western feminist priorities, and the emergence of Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN)—a network of predominantly Global South researchers and advocates who organized together in advance of the Nairobi conference—ensured that economic justice became a central feminist demand.

The NGO Forum, held at the University of Nairobi, became the true engine of debate. It hosted over 3,000 events—and was home to The Peace Tent, a space for negotiating sharp political differences.

Quechuan activist Tarcila Rivera Zea remembers the feeling like it was yesterday. “I, for instance, did not speak English and it was like being in a space where we all [twelve indigenous women from different countries] conversed with our eyes, and it was marvelous.”

“We left Nairobi filled with the realization that the truly global feminist movement which had been born during the Decade for Women was christened at Nairobi.”

–Kristin Timothy, "Walking on Eggshells at the UN,”

Developing Power: How Women Transformed International Development.

Welcome signs at the entrance to the NGO Forum in Nairobi in 1985 held at the University of Nairobi. (via Anne S. Walker)

Delegates at the NGO Forum '85, held alongside the World Conference on Women in Nairobi. (via UN Photo)

Four Women from Asia, Africa, Australia and Fiji dance at the Tech and Tools event at the Nairobi NGO Forum. (via Anne S. Walker)

New Zealand delegation welcomes chief delegate Ann Hercus with a Māori chant. (via UN Photo)

Young Kenyan women in traditional dress at the opening day of the World Conference on Women in Nairobi. (via UN Photo)

An conference participant at the NFO Forum in Nairobi. (via Anne S. Walker)

Leticia Shahani, Secretary-General of the Third World Conference on Women addresses a press conference in Nairobi. (via UN Photo)

Women crowd around for a workhop at the Tech and Tools inside the Peace Tent at the Nairobi NGO Forum. (via Anne S. Walker)

UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar opens the 1985 World Conference on Women. (via UN Photo)

Dr. Salma Maqbol, Chair of the World Blind Union’s Committee on the Status of Blind Women, meets with Leticia Shahani, Secretary-General. (via UN Photo)

An overall view of the NGO Conference in Nairobi, held alongside the Women's Conference. (via UN Photo)

There Were Challenges…

Bringing together 150 countries and thousands of women meant major ideological clashes. Many Global South activists rejected Western feminist priorities, arguing that survival—access to food, land, and jobs—was as important as legal rights. And debates over apartheid, Palestinian rights, and Cold War politics often led to fierce negotiations.

In fact, negotiations over the final conference document nearly derailed the process. As Ramos-Shahani would recount, US delegates threatened to walk out if a denouncement of “Zionism” was included in the Forward-Looking Strategies, while African and Arab groups vowed to break up the conference if it was removed. A small group of conference leaders from Kenya, Russia, the United States, Palestine and Western Europe met to strategize, faced with the very real possibility of negotiations falling apart. They decided to substitute any mention of “Zionism” with “all forms of racial discrimination.” They reached consensus—culminating in a 4 a.m approval of the FLS.

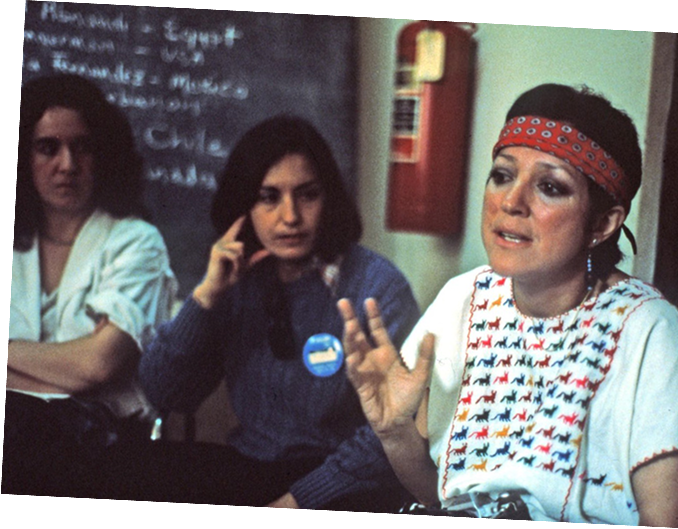

Top: A Latin American woman speaks passionately to a workshop group at the NGO Forum in Nairobi in 1985. (via Anne S. Walker)

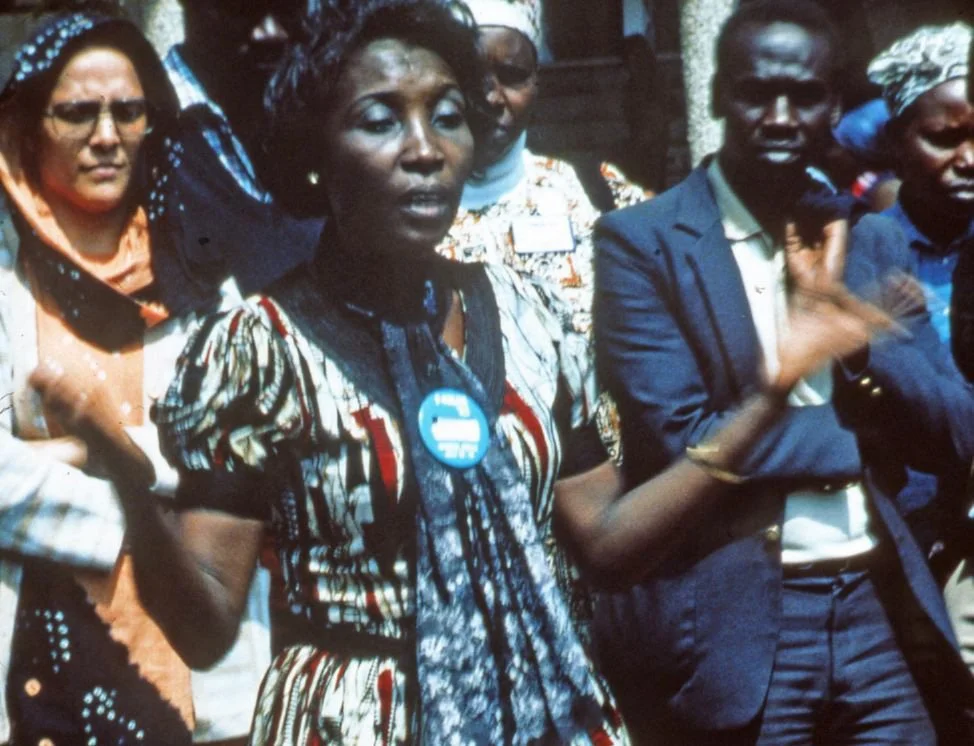

Bottom; Demonstration by Arab and African delegates during the speech of the Israeli delegate. (via UN Photo)

…And There Were Victories

The 1985 Nairobi Conference marked a turning point for the global women’s movement. It strengthened women’s movements across the Global South, especially in Africa and Asia. More young women got involved, and increased funding combined with Nairobi’s location enabled broader participation from Africa and Asia.

As a result, one big win was the wealth of research generated for the conference—giving the world a crisper picture of what had (and, in places, had not) been achieved during the UN Decade for Women. And, as Antrobus notes, unlike previous UN conferences, delegates tackled issues like violence against women and child abuse—and those issues were reflected in the FLS.

An overall view of the NGO Forum in Nairobi, held alongside the Women's Conference. (via UN Photo)

The Outcome

Nairobi is often called “the birth of global feminism”—the true launch of a movement that was shaped by diverse voices from the Global South. That energy didn’t end when the conference did; it fueled new cross-cultural alliances that shaped the women’s movement in the years that followed…especially when it came time for the next big milestone, ten years later.

The FLS set the stage for the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Nairobi made clear that gender equality and women’s rights were not separate from power, economics, and survival, but an integral part of them.

As author and activist Charlotte Bunch recalled, “It really broke open that everything is a women’s issue, and therefore feminists can have something to say about anything.”

Top: Margaret Kenyatta, President of the Conference, speaks alongside Secetary-General Leticia Ramos-Shahani and Pilar Santander-Downing. (via UN Photo)

Bottom: The Tech and Tools notice board at the NGO Forum in Nairobi in1985. (via Anne S. Walker)

Hear the stories…

The real people, friendships, battles and victories of the conferences and beyond

Learn More

Explore the documents, data, and stories of the conferences.