The Conferences

This historic convening drew over 45,000 participants from around the world. They came “to answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live.”

Beijing, 1995

The Global Mood

By 1995, the world both inside and outside the UN was different than it had been ten years earlier, when the last World Conference on Women took place in Nairobi. The end of Apartheid, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War with it, and the Oslo Accords had eased geopolitical divides; and the rise of global interconnectivity through new technologies and digital communications helped feminists connect. Women’s rights advocates and allied diplomats were able to win key victories at the early ‘90s conferences in Rio de Janeiro, Vienna, Cairo and Copenhagen. The stage was set for a powerful, expansive, and potentially more harmonious women’s conference.

Attendees at the NGO Forum held in Huairou, China. (via UN Photo)

The Planning

The women’s rights advocacy infrastructure that sharpened joint and intersectional efforts at UN conferences in the early ’90s brought momentum to Beijing through the Linkage Caucus—a coalition of activists and organizations focused on connecting women's issues with broader concerns like human rights, economic justice, environmental sustainability and social justice. Global networks and organizations like the Women of Color’s Resource Center and Isis International helped spread the word about Beijing, circulating newsletters filled with practical information, art, poetry, and personal stories, building excitement and momentum for the event. And there was funding for Beijing: The United Nations increased its financial support, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC), a group of donor countries, helped coordinate bilateral funding; and the Ford Foundation led a wide-ranging and extensive philanthropic strategy to support the global women’s movement’s engagement in Beijing, alongside the Rockefeller Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, and other private philanthropies.

Gertrude Mongella, Secretary-General of the Fourth World Conference on Women, addresses an audience. (via UN Photo)

The Players

Organizers of Beijing, including Tanzanian leader Gertude Mongella, who’d been appointed Secretary-General of the conference, were “often met with disbelief” from senior UN officials when they predicted massive turnout, one of them later recalled. But they were right! Over 17,000 participants, primarily women, gathered from 189 countries for the official intergovernmental proceedings, and almost 30,000 people attended the event’s parallel NGO forum. (Programs like “Send a Sister to Beijing”—designed to raise $1 million USD to support travel for women from marginalized groups without resources—increased enthusiasm and attendance.) And world leaders from every continent appeared. Alongside Mongella, anti-Apartheid African leaders like Winnie Mandela and Beverley Ditsie—the first openly gay woman to address the UN—emphasized intersectionality. And Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto addressed female infanticide and the rights of girls, while Chen Muhua, the President of the Beijing Conference and Vice-Chairperson of China’s National People’s Congress, reflected that the conference was “not only a cry from the women's population, but a demand from the times."

Top: Longtime friends Jane Fonda and Secretary-General Gertude Mongella embrace at the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

Bottom: Nana Konadu Agyeman Rawlings, First Lady of Ghana, speaks to correspondents during the conference. (via UN Photo)

What Happened in Beijing

At the heart of the Beijing Conference was the Declaration and Platform for Action, a massive 150-page document, with nearly 40% of the draft still requiring negotiations and consensus at the conference’s start. This complex agenda outlined a global path forward on the most critical issues facing women—economic participation and power, girls’ rights, violence against women, reproductive rights, and more—all the way through the end of the century.

The conference spanned 10 days—12 hours a day!—with a staggering 132 concurrent workshops daily at the NGO Forum. In total, there were over 3,000 events at the Forum, covering vital human rights issues like the rights of migrant women, accountability for Japanese war crimes against women, reproductive rights, and feminist concerns about new information and communications technologies and their potential for overreach and monopolies.

And the NGO Forum brought together a diverse array of participants, ranging from grassroots labor organizers to conservative religious groups. Women from East Timor, Tibet, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia advocated for the rights of women in conflict situations. Indigenous women met and developed the Beijing Declaration of Indigenous Women. Even the private sector showed up, with Apple sponsoring the very first Internet center at a world women’s conference. “To say that the NGO Forum in Huairou was vibrant would be an understatement,” wrote participant Lina Abou-Habib. “It was a magical space where feminists the world over were arguing, discussing, lobbying, showcasing, and reaching out…All of us were bringing our issues and demands to the forefront and sharing these with each other, at the most important feminist convention of the 20th century.”

Far left: Peggy Antrobus and Rhoda Reddock. Far right: Hazel Brown at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, 1995. (via UWI St. Augustine Campus)

Hillary Rodham Clinton, then First Lady of the United States, delivers her historic remarks to the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

Nana Konadu Agyeman Rawlings, First Lady of Ghana, speaks to correspondents during the 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

Activists outside the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via Georgetown University Library)

Ambassador Madeleine Albright, First Lady Hillary Clinton, and the U.S. Global Conference Secretariat meet with U.N. Secretary-General Gertrude Mongella to advance conference preparations. (via Georgetown University Library)

A woman learns to use a computer at the 1995 NGO Forum in Huairou. (via Anne S. Walker)

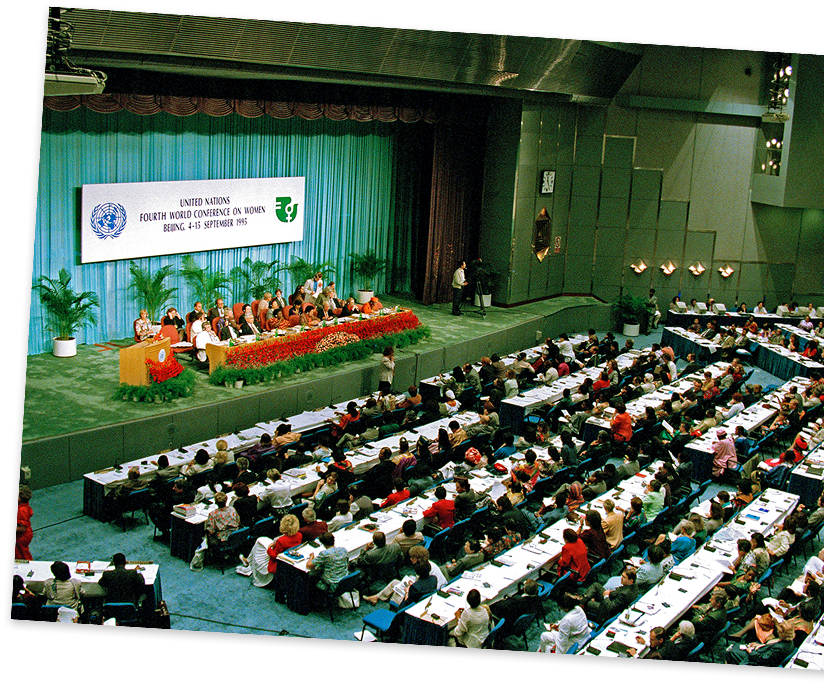

The opening ceremony of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

A Chinese woman in a wheelchair speaks with a young woman at the NGO Forum in Huairou. (via Anne S. Walker)

Inside the Main Committee’s marathon meeting at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

Delegates work late into the night on the Draft Plan for Action. (via UN Photo)

Scene from the NGO Forum in Huairou. (via UN Photo)

Two young attendees observe the Youth Day opening celebration. (via UN Photo)

A packed Plenary Hall as Hillary Rodham Clinton speaks at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

There Were Challenges…

One of the greatest logistical and political hurdles of the Beijing conference centered on the location of the NGO Forum—which, at the last minute, was moved to Huairou, a suburb of Beijing, a full 50km away from the official intergovernmental conference venue. The Forum site was still under construction when the Beijing conference began, with makeshift tents set up in mud after a heavy monsoon season, making navigation difficult, especially for people with disabilities. Additionally, visa issues prevented thousands from attending, and the Chinese government enforced heavy surveillance at both the conference and the forum, creating a sense of unease and concern over the UN’s commitment to political sanctuary.

As a result of all that, some media outlets focused their attention on collapsed tents, security issues, and questions about China instead of the conference's broader goals. Women around the world debated the ethics of attending at all. Still, as Charlotte Bunch, Mallika Dutt, and Susana Fried of the Center for Women’s Global Leadership noted, “…the numbers who entered the debate reflected how seriously women took this event. Understanding the need for global solidarity, women decided to show strength of the movement by attending in spite of the obstacles posed by the site.”

Ahead of Beijing, backlash to the global women’s movement had emerged in the form of a global conservative religious and fundamentalist countermovement; it began as a reaction to the success of women’s human rights defenders at the 1993 Vienna conference and gained momentum during the preparations for the 1994 Cairo conference. At Beijing, a group of conservative Member States moved to block progressive language in the Platform for Action around reproductive rights, girls’ rights, inclusive families, sexual orientation, and the term “gender.”

Top: Participants at the NGO Forum in Huairou, held alongside the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

Bottom: Informal discussions during the main committee meeting at the 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. (via UN Photo)

…And There Were Victories

First and foremost, the Beijing conference resulted in 189 countries agreeing to the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which outlined 12 critical areas for advancing gender equality and empowering women globally. The platform was comprehensive and confident: It urged governments to tackle poverty's disproportionate impact on women, to ensure access to education and healthcare. It called for action on domestic abuse, demanded more representation by women in political decision-making and climate action, and pushed for better media representation of women. Progressive language on reproductive rights and girls rights remained, as did the term “gender.” Finally, the PFA highlighted the need to empower women in peace-building and conflict resolution.

The PFA was a progressive milestone for intergovernmental agreements on gender equality. While it was non-binding, it laid out a clear roadmap for action on gender equality. And it was a forceful statement about the urgent need for equality and for justice. Its intended impact was perhaps best captured in then-US First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton’s historic speech: “If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.”

Or as “Mama Mongella” put it: “It is not by chance that the time has come for women to receive their rightful place in all societies and be recognized once and for all, that they are no more guests on this planet. This planet belongs to them too.”

Scene from the NGO Forum in Huairou. (via UN Photo)

The Outcome

Beijing is widely seen as a major success for the global women’s movement, for regional and grassroots organizing, and for intersectional feminism on the world stage. It led to a proliferation of national laws on gender equality, new ministries and institutions focused on gender and women’s issues in national governments, increased women’s political participation, and rich cross-pollination and connection between women’s organizations and networks. However, significant global shifts following Beijing meant that the implementation of Beijing’s vision and its momentum would struggle.

In her closing statement to the conference, Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland reminded delegates, “We came here to answer the call of billions of women who have lived, and of billions of women who will live…Undoubtedly, we have moved forward. But the measure of our success cannot be fully assessed today. It will depend on the will of us all to fulfill what we have promised. The story of Beijing cannot be untold. What will be remembered?”

Hear the stories…

The real people, friendships, battles and victories of the conferences and beyond

Learn More

Explore the documents, data, and stories of the conferences.